The bigger picture

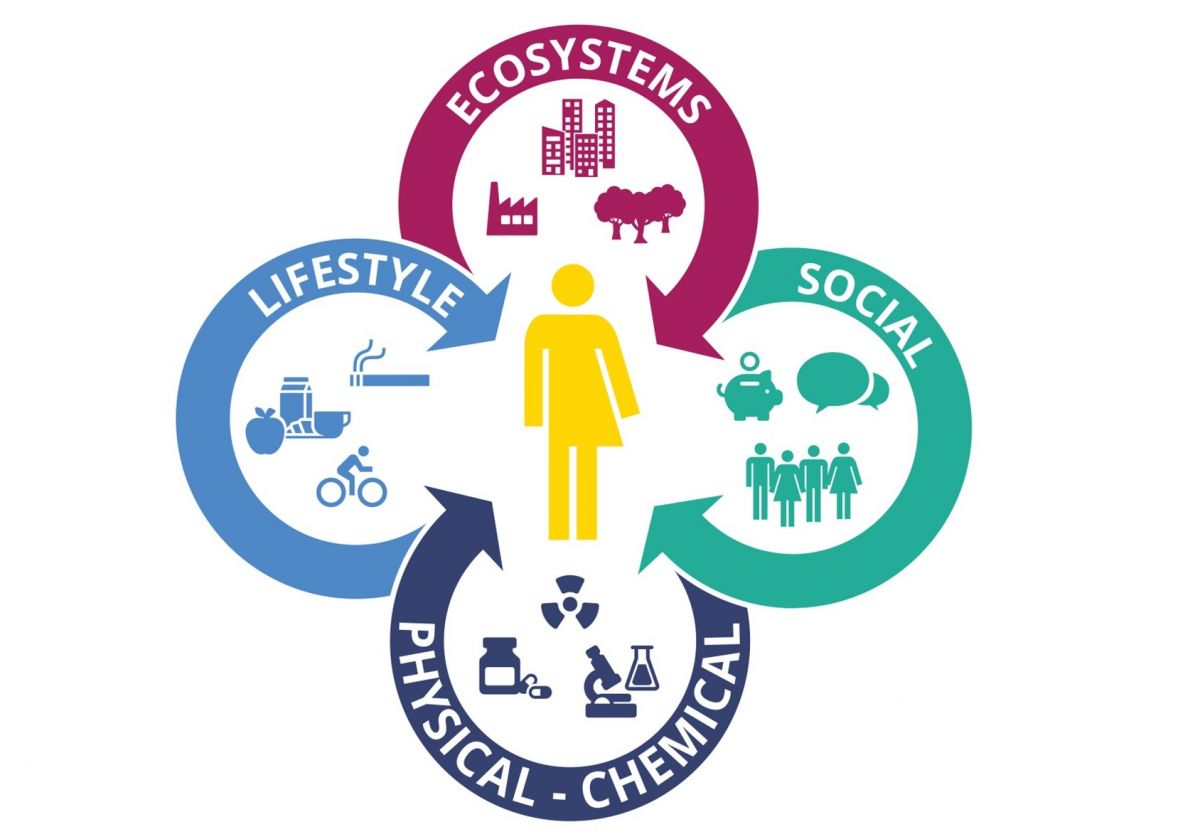

‘The exposome’, this is the term for everything that we are exposed to from birth to death. Think about the air we breathe, the food we consume or the surfaces we touch. And since it is literally everything, the list goes on and on. Although we now come to realize that heavily processed foods or the ingredients in our skincare products might be bad for us, many products contain harmful chemicals that we are not even aware of. What does cooking on Teflon-coated pans or living next to a busy road do to us in the long run?

Given the multitude of environmental exposures, how and where do you begin to entangle their effects on our health? Epidemiologist dr. Virissa Lenters (UMCU) is part of the Utrecht Exposome Hub, she has taken on the ambitious task of answering some of these questions. She is especially interested in how urbanization and the increase of air pollutants affect our health and wellbeing.

NATURE AND NURTURE

It is one of the oldest debates in science: are health and behavior shaped by our genetic makeup (nature) or our environment (nurture)? Whereas the relative contributions of nature and nurture were often discussed from a one-sided approach, scientists now realize that it might be a joint achievement. Height for example, is a personal trait that is influenced by the interaction between the two. If someone is born into a tall family, they might have inherited those genes and grow out to be equally tall as the parents. However, if they grow up in an environment with a lack of nutrition, they might never reach the same height.

So, one impacts the other. Twin-studies have shown that this interaction between nature and nurture sustains throughout life. As identical twins share genes, their nature is comparable. Although they look the same from the outside, both their health and personality often differ based on individual experiences. This holds true for most chronic diseases that we are familiar with, ranging from asthma to leukemia. Only 15% of the causes of these diseases are heritable, the rest can be attributed to, often unknown, environmental exposures. This is where exposome science comes in.

DECODE THE EXPOSOME

The genetic influence on health and disease has been a prominent research area for decades. However, exposome science only became a scientific field around 2005. Unlike genetic research, measuring someone’s environmental exposures requires a multi-disciplinary approach that captures the full complexity of the exposome. “We aim for a holistic approach, in which we characterize all exposures in a comprehensive way. This contrasts the more traditional approach, where you would relate one exposure to one disease risk.” explains Lenters. Due to recent technological advances, this research field has taken a big leap forward. Scientists can now use satellites, modelling, wearables and sensors to study the exposome in its entirety. A relevant example is the wrist-worn temperature sensor that can be used for early detection of COVID-19. Or think about the mushroom-shaped sensors that are currently up and running at Utrecht Science Park and measure real-time air quality conditions. By combining this with biomedical measurements of bodily fluids like blood or urine, scientists can link external exposures to internal outcomes on a functional level.

‘MAGICAL MICROBES’ IN OUR GUT

A perfect intersection between our external and internal worlds is represented by the gut microbiome. This is a collective term for all the bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa in our intestines. It is a relatively new field, but it quickly became clear that the gut microbiome plays a big part in our health and wellbeing. Bold headlines made the papers in the past years: ‘Is your gut microbiome the key to health and happiness?’ or ‘Magical microbes – how to feed your gut’. Although she does not use the word ‘magical’, Lenters agrees that the gut microbiome holds potential: “The trillion bacteria in our gut are very important for us. For synthesizing vitamins, helping us digest our food or for priming our immune system. They play a key role in many immune-mediated diseases, cancers and neurological disorders.”

In her research, Lenters particularly focusses on how urbanization affects our gut microbiome, and as such, our health. Since the majority of people live in cities, many aspects of modern human life have changed: our diets, our living environments, our stress levels or the levels of air pollution. The gut microbiome has co-evolved, and not necessarily for the better. On a global scale our bacterial diversity has decreased, mainly because the levels of chemicals increased with urbanization. So, is it all bad news? And what can we do about it?

SHAPING OUR ENVIRONMENT

So should you pack your bags and move to the countryside? Lenters reassures us that is not necessary: “We also found factors that counteract the negative effects of air pollution. Owning a dog or a cat, for example. Or the greenspace surrounding your home or workplace. The more biodiverse your surroundings are the more biodiverse your microbiome is.” These research findings inspire the development of targeted interventions. On a local scale, green buffers between a busy street and a terrace can act as pollution barrier. But Lenters and her colleagues have bigger plans: a publicly accessible exposome map, like a Google Maps for environmental risk factors. In Utrecht this is already being realized with the Air View Car, an electric car with mobile sensors that creates interactive pollution maps.

So, although exposome science is only at its infancy and will undoubtedly face complex challenges in the future, the interdisciplinary scientists at the Utrecht Exposome Hub aim high. Because as leader Prof. Roel Vermeulen states in a recent background article from the UU: “We can’t (easily) change our genes, but if we are serious about the prevention of diseases, we need to know the modifiable part – that is, the environmental factors.”