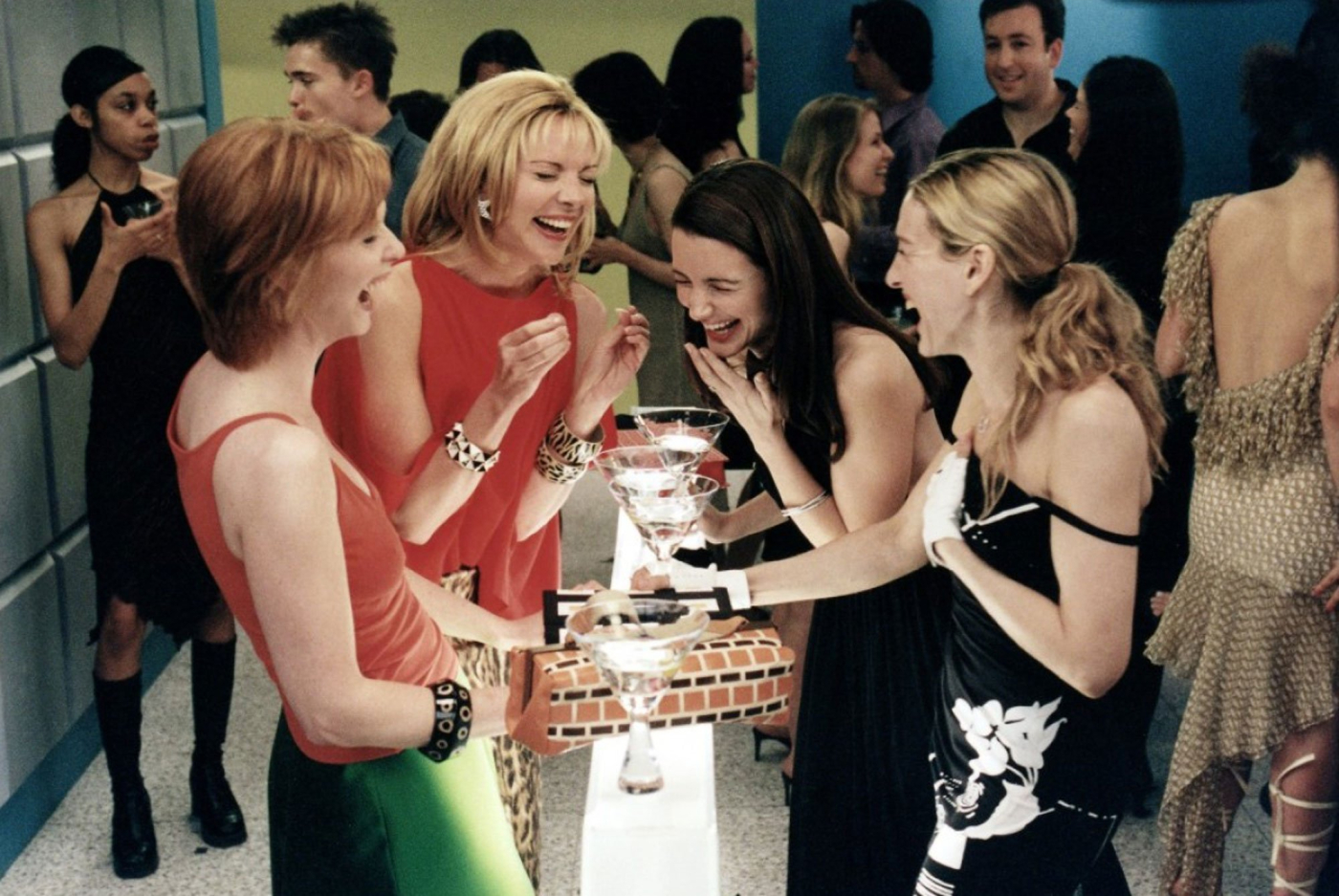

Let's talk about sex, baby

Scarcely dressed women in music videos, lustful lyrics, and blockbuster movies with intimate scenes involving blindfolds and whips. These images are familiar and popular, but also the target of criticism. In the series Pop Culture Matters we examine the role of pop culture in society. In the first lecture media and communication scholar dr. Linda Duits (UU) talks about sex on screen. Duits problematises the critique offered by psychological research, such as the APA (American Psychology Association) taskforce report. This study claims that sexualised pictures paint women as unresisting sexual objects, thereby enforcing the 'wrong' attitude towards sexuality and even spur sexual promiscuous behaviour. Do we develop sexual standards based on what we see in the media? Are movies, TV-shows and video clips really that powerful?

Concerns about the sexualisation of girls

In the middle of the 2000s, there was a growing concern in several western societies about sexualisation in the media. Think for example about the Dutch word 'breezerslet', a derogatory term for a young, easy going girl who performed sexual favors in return for a sugary alcoholic drink. Supposedly, these girls got the idea from music videos. In the United States the APA decided to investigate the 'sexualisation of girls'. First, the researchers did content analysis - what can we see? Sitcoms include sexist remarks, music videos contain sexual innuendo and the lyrics are sexually degrading ("I tell the hoes all the time, bitch get in my car" - 50 cent). There are movies with sexual themes, magazines with articles that tell girls that they should attract the attention of boys by looking hot. There is objectification of female bodies in sports media and advertising. The list goes on and on. And according to the report all this impacts girls' health and well-being. They mention symptoms such as diminished cognitive and physical functioning, body dissatisfaction and appearance anxiety, eating disorders, low self-esteem and sexuality issues.

The report also notes that exposure to mainstream media encourages girls to objectify women and to see other women as less than human. Heavy stuff. But the situation is not completely hopeless, according to these scholars. They propose media-challenging solutions. Such as athletics to improve girls' self-esteem, or participation in youth clubs like the girls' scouts and marching bands. Also dancing (probably not pole dancing...) and even abstinence are presented as effective means to combat the negative impact of sexualised images on girls. A very prominent media-menacing tool the psychologists propose, is to provide girls with media literacy.

Media is not an injection of ideas

Duits, however, takes issue with this psychological approach. She thinks it defines sex too much in terms of health and what 'good sex' should be. More importantly, these psychologists test media effects through laboratory experiments that cannot possibly recreate the real-life circumstances that determine the way we consume media and are influenced by it. Another academic approach focuses on 'meaning-making'. It doesn't start from the idea that there is only one definite way in which media affect people, like the psychological approach, but rather considers pop culture as a relational object. Something we give meaning to on a daily basis, bringing all of our previous experiences, political preferences, and beliefs to the table. While an adolescent might grasp the sexual content of the Britney Spears song "Oops, I did it again", a six-year old girl probably won't. And if people know Miley Cyrus as the 'good' Miley from the Hannah Montana tv-series, they are more likely to find her nude appearance in the Wrecking Ball music video shocking. Also, the definition of what is 'sexy' or 'sexualised' differs from person to person, and determines the way people judge Cyrus' nudity. So if we accept this relational approach, it becomes very hard to pinpoint any general effects of so called 'sexualised' imagery.

Definition

The point Duits continuously emphasises throughout her lecture, is the lack of a shared definition of what 'sexualisation' is. If there is no general definition of 'sexual', there is no clear object of discussion, and without a distinct object, there can be no easy way to examine the topic empirically. Duits points out that an intersectional approach is needed to fully appreciate the diversity of the matter. What are the politics and moral judgments behind the evaluation of sex on screen?

Duits likes to talk about sexual scripts: blueprints and guidelines for what we define as our sexual identity. The media shows us a number of sexual scripts, describing how, when, where, with whom, why, and with which motivations we are sexual beings. In real life there are many sexual scripts, while on television their number is limited, the most dominant ones being heterosexual and monogamous. How audiences read these scripts, and how they are affected by them, depends greatly on who they are.

All talk

Although the debate on sexualisation, sexual objectification and pornification returns every few years, the discussion is extremely difficult. There is a lack of definition, and different scholars have different ways of studying the matter. It's almost impossible to avoid moral judgments on sex, since there is always fear of young people in engaging in it, especially in the United States where much of these studies are conducted. Additionally, it's hard to avoid politics, we cannot escape a discussion on sexism, racism, homophobia and other axes of oppression when we talk about sex on screen. What about boys, for example? Concerns about sexualisation of the media are almost exclusively focused on girls, and there is often no evidence for these claims. Duits does not believe that media literacy is a must for young people, since developments within the media are too quick for any teacher or curriculum to grab. What's more, many girls (and boys) already are media literate and, having knowledge about the ways and influence of media does not necessarily change behaviour. Talking about sex is important, but difficult. Sometimes it's easier to just do it.

You can watch the full lecture here

On March 9 is the second lecture in this series, with media scholar Abby Waysdorf (EUR) sharing her research on film tourism. Why do so many people travel to locations from their favourite books, films and shows? More info.